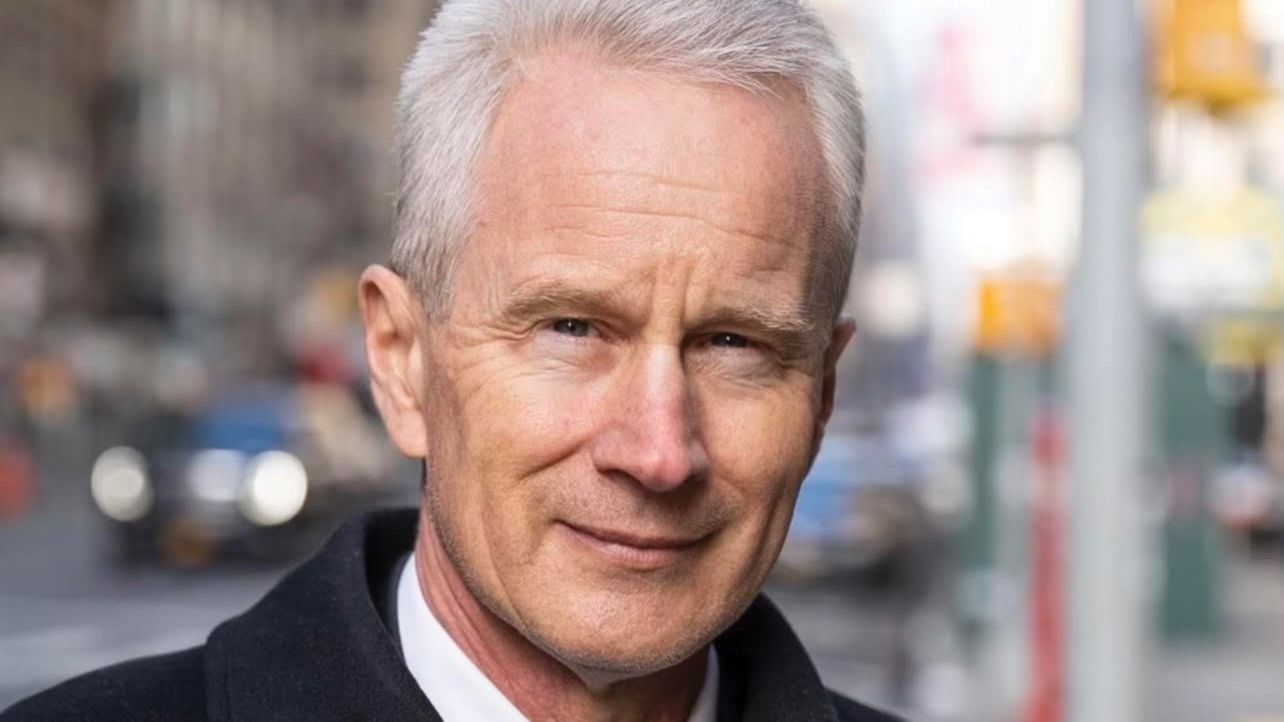

An Interview with Kat Mische Elle

Dr. McCullough, where did your story begin?

I was born in Buffalo, New York, and my family was a middle-class working family; my dad worked in a factory, and my mother was a primary homemaker. Our world was rocked when I finished my first year of high school, and the economy plunged into a recession in 1975. My dad lost his job when the factory was shut down, and our family went on a downward economic spiral. My family packed up the car, and we moved from western New York state to Texas. When we crossed the Red River at Wichita falls, we set up our family shelter in a hotel room. Our family made it to the Dallas, Fort Worth area, and my father secured a long-term job with Abbott Diagnostics, which he held until his retirement.

I was one of 3 boys, and I was the middle one. Every dollar we ever spent since I was the age of twelve, we each made on our own. And that includes selffunding—especially every car, tuition dollar, dorm payment, and every meal. That type of self-reliance that comes out of hardship is durable and supports a sense of personal self-efficacy to the extent that my brothers and I’ve never considered the idea that we would be reliant on anyone else.

I think this is very important to be self-reliant.

I knew that I could have everything stripped away from me down to nothing, and I could build myself back up again.

What were your first jobs? When did you start to notice that you were interested in going into medicine?

The first jobs were just anything that could pay money. My brothers and I started delivering newspapers, washing dishes, making beds, and stocking shelves. We did all types of jobs to make money. But the goal to make money was to be able to afford the education we needed to take the next steps in life.

When did you start to notice that you were interested in going into medicine?

I was always drawn to science, and I knew I liked working with people. So going in the direction of medicine was the perfect blend of both aspirations, and I never considered another career.

I didn’t have a backup plan. I was going to go to medical school.

I started college at seventeen. I attended Baylor University in Texas, the oldest university in the state.

And then right into medical school at age 21, I was accepted to the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas.

Because I had already been working since 12, I knew how to work during the day and study at night. Those habits were deeply ingrained in me, and I considered them very important.

I learned over time that physical and mental strength was significant to success. I never ran out of energy or got to the point where I said, “Well, I can’t read another chapter.”

My mind was set with the goals in front of me. Each day I would tell myself, “I’m going to read another chapter, then I’m going to read one or two more after it, then I’m going to make some more notes.

After that, I’m going to go back to what I have read and then I’m going to ask myself questions to see what I learned from what I read.

Then I’m going to close the book, and I’m going to get a piece of paper to draw out all the chemical reactions and make sure I got them right. I will double-check those results, and then I will be done.

This was my regular daily study routine all through school.

I would look at exams almost like an athletic challenge. It was something I would get pumped up and psyched up for. And when I looked at the exams, I would say, “I want to crush it, Not just pass it.”

What were the next adventures for you after you graduated from medical school?

After college, I strongly desired to see another part of the country, so I applied for residency and was accepted at the University of Washington in Seattle.

This was a time when two crucial life steps were happening for me.

It was 1988, and within two weeks, I graduated from medical school, got married, and started my residency at the University of Seattle.

My wife and I dated for a while, then we had our wedding, took our honeymoon, and took an apartment in Seattle to live together for the first time.

This was back when you didn’t live with your significant other before you were married.

A lot of great adjusting was taking pace.

Seattle was where a small local coffee shop chain called Starbucks was a neighborhood favorite, and a small tech company was forming called Microsoft.

This area of Seattle was charming during those years. It was far from everyone but just enough city life to get things done.

In the 1980s, it was common for many graduates at The University of Washington to do service. Many of my fellow residents became CDC officers, which is quite interesting.

I then found an opportunity to be of service in rural health and decided to intern there for two years. I was assigned to be in the northern part of the lower peninsula in Michigan.

I joined an excellent doctor from Duke University there, and we were the only two internists for an area of about 40,000 people.

We experienced a lot of illnesses surfacing, and he and I were at the forefront of being able to help the people in this poor rural area. For my third intern year, I negotiated to move down to Ann Arbor and enrolled in graduate school at The University of Michigan School of Public Health.

At that time, I knew I loved clinical medicine, but I wanted to have an area of focus and expertise. This was also when modern computers started to come into medicine.

Before 1990, we didn’t have advanced statistical methods to easily search and review case studies because computers for the medical profession were not mainstream. The medical journals at this time were only a paper and pencil accounting of data in tables.

Before modern computers, people didn’t realize how hard research was.

I studied Survival Analysis and Multiple Logistic Regression and got the fundamentals of Epidemiology. And then, I went right into my Cardiology fellowship at William Beaumont Hospital in Southeast Michigan (now the Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine).

Through my years of study, I continually reflected on how important my time in the rural health service was and how I could leave the ivory tower of academic medicine to see a more extensive scope of things in the field from a medical perspective.

Being able to go out into the field, return to graduate school in the ivory tower, and do my fellowship in an academically oriented community hospital were critical steps taken in my life because I learned that the ivory tower is not the only place where clinical medicine and research could be done.

I continued forward and had a leadership career in Southeast Michigan. I became the Chief of Cardiology for a while in Kansas City and developed my area of expertise, which was the interface between heart and kidney disease. Because I had that broad-based experience, I was willing to reach across the aisle to nephrologists. We innovated new in-vitro diagnostics, therapeutic approaches, and clinical strategies.

I was often called upon because I was versatile by the National Institutes of Health in several branches, either as an advisor, principal investigator, leading data safety, or monitoring medical boards. I developed an expertise in the 80s with leading data safety monitoring boards for Big Pharma and the NIH (National Institutes of Health) because data safety often goes beyond a specific discipline.

Can you explain the importance of this?

When a patient is in a research study and a new drug is given, there is a possibility of a reaction such as a dermatology condition or allergic pneumonitis, a pulmonary condition in response to the drug.

I realized data safety monitoring had become a critical part of clinical trials. Any drug administered to the public should have extensive clinical trials to verify its safety and efficacy.

This led me to my final academic job, which was in Dallas, Texas, at a large academic medical center. I was then clipping through my career and was at the most senior level of what I was doing as program director. I had a wonderful blend of academic travel with the supervision of doctors and training with direct patient care, and I lived two miles away from the medical center. For me, my life couldn’t be better.

And when the SARS-COV-2 outbreak and COVID-19 crisis hit, everything went upside down. Nothing made sense within a matter of days and weeks.

Everything I knew to be true was suddenly very confusing.

The Doctors and the medical institutions were told that a tidal wave of patients was coming our way.

We shut down the cardiac catheterization laboratories and the operating rooms, sent people home, preparing to be wiped out, and then nothing happened. But we stayed prepared. I launched in a brief and very extensive research program on COVID-19 and set up methods to prevent the illness, treat it actively, reducing hospitalization and death.

I saw that this information was filling that gap about that middle part that seemed missing in treating patients.

So, I thought that was an excellent area to invest my time in, and I did so. Here we are two years later, after being hit by the pandemic.

Do you have a favorite saying to help keep your focus?

You know, I’ve come up with my line.

Be bold and relentless. It’s the only way to get things done.

Is there a particular person who has inspired and influenced your life?

The person who influenced me is Robert F. Kennedy. I was at an event with him once, and he said something that stuck with me in front of a large group. He said, “The Kennedys were told as children that there could be no greater honor than to be alive during the time of great controversy and to play a role in resolving that crisis.”

And that’s precisely where I view myself now.

What is the best way for people to find and follow you?

Please pick up a copy of my new book Courage to face COVID-19. You can find it at ouragetofacecovid.com also available on Amazon.

My link tree is: PeterMcCulloughmd.com. You can find the McCullough Report on America Out loud Talk radio for my weekly podcast. I can also be found on all social media platforms.

Through my years of study, I continually reflected on how important my time in the rural health service was and how I could leave the ivory tower of academic medicine to see a more extensive scope of things in the field from a medical perspective.